Ready to build your own Founder-Led Growth engine? Book a Strategy Call

Frontlines.io | Where B2B Founders Talk GTM.

Strategic Communications Advisory For Visionary Founders

Actionable

Takeaways

Embrace Government Funding:

Early-stage non-dilutive funding from government contracts, such as SBIRs, can be crucial for developing complex technologies and gaining credibility.

Flexibility in Technology Application:

Maintain an open mind about how your technology can be applied across different markets, which can uncover unexpected opportunities.

Storytelling and Visibility:

Actively participate in industry conferences and tell your story to attract partners and investors. Transparency and visibility can drive significant interest and opportunities.

Strategic Partnerships:

Collaborate with organizations that align with your strategic goals to bring in revenue and continue developing your core technology during challenging times.

High-Power Market Focus:

Identify underserved niches within your industry where your technology can offer significant advantages, such as the high-power market in satellite systems.

Conversation

Highlights

When Your Furnace Becomes Your Business Model: CisLunar’s Accidental Product Discovery

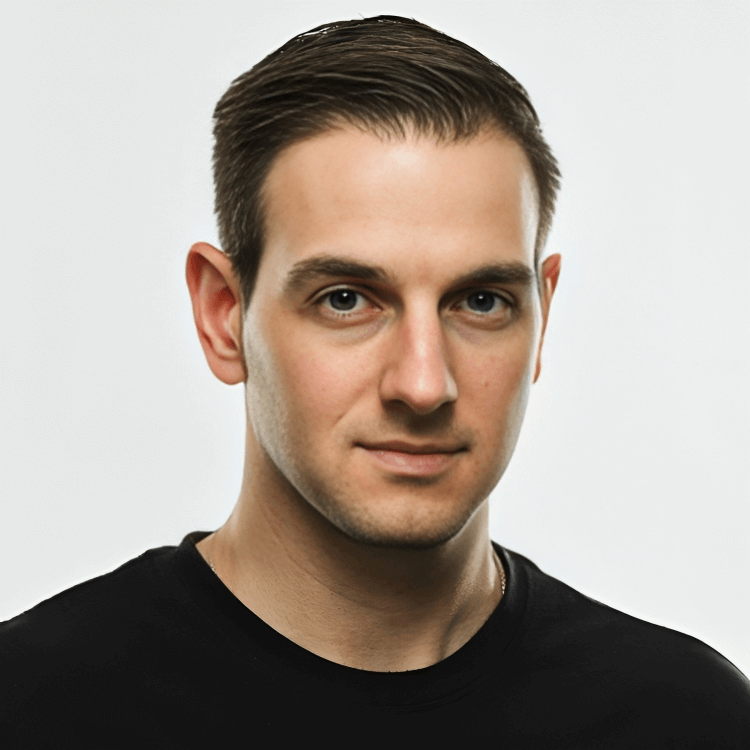

Space debris is piling up in orbit at an exponential rate. Over 10,000 objects circle Earth right now, and that number could balloon to 100,000 satellites within a decade. For most people, that’s an abstract problem. For Gary Calnan, CEO and Co-Founder of CisLunar Industries, it became an unexpected mining opportunity—and then something completely different.

In a recent episode of Category Visionaries, Gary shared how his company evolved from space metal recycling pioneers to power systems manufacturers through a discovery that fundamentally changed their business. What started as a component they needed to build for themselves became their primary commercial revenue driver.

The Discovery

CisLunar started with an audacious vision: become the steel mills of space. Gary saw millions of kilograms of refined metals already in orbit—dead satellites, spent rocket stages, debris—and wondered why anyone would extract virgin ore from asteroids when perfectly good materials were floating overhead. “We can be the steel mills of this industrial economy,” Gary explains. “Space debris is a problem today, and it’s also potentially a resource.”

The company won its first NASA SBIR contract in 2021 to develop a metal recycling foundry. The technology relied on electromagnetic induction to create heat in metal and control it without physical contact. But there was a problem: every off-the-shelf power converter they could buy was “big and expensive and not really designed or ever would be designed to go to space.”

So they built their own. It was about the size of a toaster oven.

Then they hired a brilliant electronics engineer who shrunk that toaster oven-sized power converter down to the size of a deck of cards. Same power output. Radically different form factor.

What happened next changed everything. Gary and his team showed their miniaturized power converter to a collaborator at Colorado State University. The response: “You know what, guys? This thing looks a lot like a power processing unit for propulsion and for other things, too, that people need in space.”

That observation sparked a realization. “Everything in space, all the satellites you see, except for when you light the rocket with chemical propulsion to send it somewhere, everything else is electrical,” Gary explains. “Electricity is coming from solar panels or maybe a nuclear reactor or some battery or something. And then it’s being transformed from the state that it comes from that source…transformed into a different type of voltage and amperage and frequency to be used in another use case.”

Thrusters. Welding applications. Satellite buses. Radio transmitters. The entire space industry runs on power conversion, and CisLunar had accidentally built a component with “potential applications across the entire industry.”

Navigating Two Markets Simultaneously

Most founders struggle to find product-market fit in one category. Gary is building two businesses at once, each with radically different time horizons and customer bases.

On the metal processing side, CisLunar has positioned itself as the leader in recycling and processing metals already in space. But Gary is realistic about the timeline: “The commercial time horizon was quite distant, like probably a decade out for metals and materials to be really a big commercial market in space.”

That decade-long horizon creates a problem for traditional venture capital. “One of the big challenges we’ve had with your typical investor, VC investor, is that our time horizon to get to commercial viability for metal processing is not your typical five to seven years,” Gary notes. “And that just doesn’t fit with the turnaround time that most VCs typically say they need.”

The power converter business solves that problem. While government contracts fund metal processing R&D, the power systems create near-term revenue. “The power converter business will drive commercial sales and help us to grow the company on a commercial basis over the next few years,” Gary says.

CisLunar targets the higher power segment—one kilowatt and above—where few manufacturers operate. Their modular, Lego-brick approach lets them scale systems up or down depending on customer needs, creating a differentiation advantage against established players.

Surviving Without Venture Capital

For years, CisLunar survived without institutional funding. They closed their first VC investment in Q1 of this year, having previously relied on friends, family, and angel investors for $1.2 million.

“We even took contract engineering deals with some customers who were aligned with us strategically and where we were helping them with things that were complementary but not what we wanted to be working on for ourselves,” Gary shares. “That allowed us to bring cash in the door and even hire people new to the company even though we couldn’t raise money.”

That scrappiness matters in hardware-intensive deep tech, where capital requirements are high and commercial timelines are long. Gary watched the SPAC boom come and go, then weathered the VC downturn that followed. But government support provided the traction that eventually attracted investor interest.

On the government contracting process itself, Gary offers encouragement to founders intimidated by bureaucracy: “Most intelligent people running businesses…can figure out how to navigate if you want to.” He was particularly impressed by the Space Force: “They’re trying to be adaptable to the industry as it is, and take advantage of the benefits of entrepreneurship. And they’ve moved pretty fast, and they’ve been very helpful and collaborative with us.”

The Long Game

CisLunar’s three-to-five-year vision involves growing from 15 people to 50-70 employees while establishing themselves as essential infrastructure providers for the cislunar economy.

Gary’s advice to aspiring space tech founders cuts through the romance: “There are easier ways to make money from an entrepreneurial perspective. So you really have to be bought into this to go through the long ups and downs.” But for those with genuine passion, he recommends getting out and telling your story early. “We decided not to go stealth from the very beginning,” Gary says. “Making contact with the market is always better to refine your idea and…be willing to be flexible and open to changing paths.”

That flexibility—the willingness to see opportunity in a deck-of-cards-sized power converter originally built for a completely different purpose—exemplifies the adaptability that separates surviving companies from failed ones. CisLunar didn’t abandon their vision of becoming the steel mills of space. They just found a way to fund that decade-long journey by solving a more immediate market need.

Sometimes the best product strategy isn’t the one you planned. It’s the one you discover while building something else.