Ready to build your own Founder-Led Growth engine? Book a Strategy Call

Frontlines.io | Where B2B Founders Talk GTM.

Strategic Communications Advisory For Visionary Founders

Actionable

Takeaways

Design around regulatory arbitrage, not reform:

Intersect's entire business model targets unregulated spaces. Sheldon rejected the conventional utility PPA path, stating: "We built a business model that is not go right at something." Their behind-the-meter, off-grid approach operates outside state public utility commissions, FERC jurisdiction overlaps, and ISO/RTO coordination failures. When entering regulated markets, map the jurisdictional gaps and build your product to live in those spaces rather than fighting for reform that won't come.

Bet on technological disruption of calcified systems:

Sheldon explicitly compared the grid to the Bell System, which wasn't reformed but rendered irrelevant by cellular, fiber, and digital infrastructure. He observed: "Nobody inside the regulated telecom industry said, let's fix this. Brand new technologies just completely gutted it from the inside out." When facing entrenched infrastructure with misaligned incentives across fragmented stakeholders, identify the technological bypass rather than incremental improvements. The constraint that makes reform impossible also creates the asymmetric opportunity.

Optimize for project scale, not team expansion:

Intersect maintains radical efficiency by building only gigawatt-scale projects with lean teams. Sheldon's framework: "It takes the same number of people in contracts to build a gigawatt plant as it does to build a hundred megawatt plant, so you might as well build the bigger one." This isn't generic "do more with less"—it's identifying which costs are fixed regardless of project size (legal, interconnection applications, permitting) versus variable (construction materials). B2B founders should analyze their own cost structure to find similar leverage points where deal size scales independent of resource requirements.

Lock major contracts before infrastructure deployment:

Intersect's capital strategy starts with hundreds of thousands for land options and interconnection applications, uses early reputation to secure anchor contracts, then raises billions in non-dilutive project financing against those contracts. Sheldon described it as: "Making enterprise software where your first sale was to 10 Fortune 500s and they took everything you could possibly build for the next five years." The contract becomes the collateral for low-cost debt financing. For capital-intensive B2B models, structure early sales to de-risk the bulk of your capital deployment.

Identify where constraints migrate in your value chain:

Sheldon analyzed the AI infrastructure stack from dirt to chips and concluded: "For the next decade, there'll be a constraint in the physical infrastructure. It'll need cloud providers that have access and expertise to build infrastructure and achieve capital formation around infrastructure." Value accumulates at bottlenecks. Neo clouds like CoreWeave started at the model layer and are pushing down; Intersect started at power and is pushing up. Position your product where the constraint is moving, not where it currently sits. This requires continuously modeling your industry's supply chain physics.

Let unit economics override industry narratives:

While energy policy debates favor nuclear and central-scale combined cycle gas plants, Intersect's math shows their hybrid approach—flexible reciprocating engines and aeroderivative turbines with renewables and batteries—delivers power at a fraction of the cost. Sheldon noted alternatives run "$120-150 a megawatt hour versus most people paying $30-40." He emphasized: "It's just math and it's not hard math." Strip away conference circuit consensus and regulatory capture. Model actual delivered unit economics, then let superior economics compound into strategic advantage while competitors chase policy-driven narratives.

Conversation

Highlights

How Intersect Bypassed the Broken Grid to Build Gigawatt-Scale AI Infrastructure

The US power grid has a Balkanization problem that no amount of policy reform will fix. State regulators, federal agencies, and regional system operators operate as competing fiefdoms, each refusing to coordinate on transmission buildouts that would move stranded energy from West Texas to data centers in Virginia.

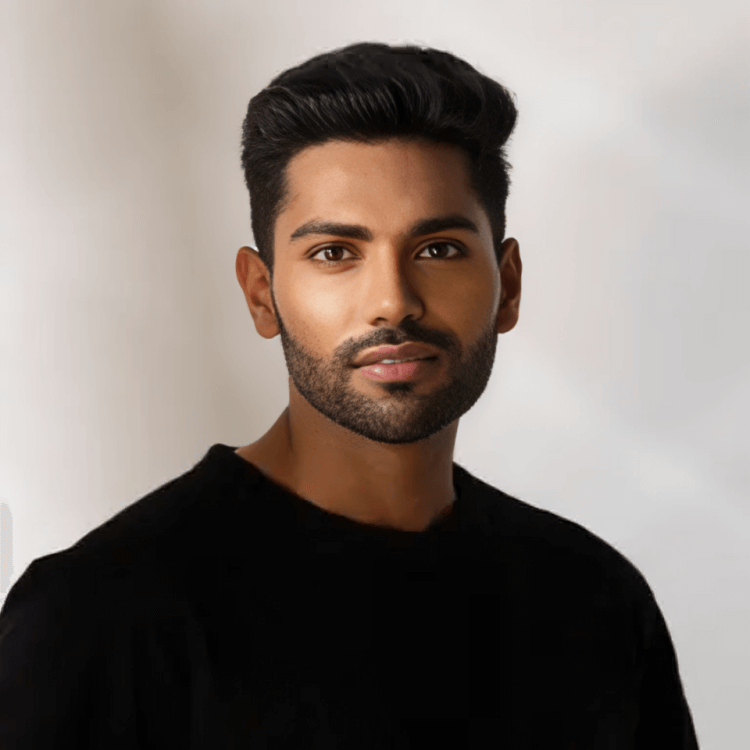

In a recent episode of Unicorn Builders, Sheldon Kimber, CEO and Founder of Intersect, explained how his company solved this by ignoring the grid entirely. Currently constructing $9 billion in assets with another $10 billion breaking ground in 2025, Intersect builds gigawatt-scale power plants and develops behind-the-meter data centers directly adjacent to them. No transmission. No multi-jurisdictional regulatory battles. No constraints.

The Structural Problem That Can’t Be Reformed

After selling Recurrent Energy to Sharp Electronics, Sheldon spent two years thinking about what came next. He had a thesis for a software company in the energy space, but a VC friend told him bluntly: “You’re not a software executive. Go build something big. Go build it in steel.”

The insight that shaped Intersect came from analyzing why the grid couldn’t be fixed. “The grid is hopelessly broken and no one’s going to fix it,” Sheldon said. The problem wasn’t technical capacity or even permitting complexity—it was fragmented governance with misaligned incentives.

“It’s regulated at the state level, it’s regulated at the federal level. Then there’s these things called regional system operators, ISOs, RTOs,” Sheldon explained. “All of them kind of abut each other and none of them want to play ball with each other.”

Republican governors in western states refuse to coordinate with California. Regional system operators can’t agree on interconnection standards. Utilities sitting next to each other won’t share planning data. The result: abundant solar, wind, and natural gas trapped in locations with no economically viable transmission path to load centers.

Sheldon drew a parallel to the Bell System: “Nobody inside the regulated telecom industry said, let’s fix this. Brand new technologies just completely gutted it from the inside out, made it almost irrelevant.” Cell phones, fiber, and digital infrastructure didn’t reform the existing system—they rendered it obsolete.

His bet: “We just made a big bet that the load, the users of energy were going to come to the energy because no one was going to bring them a pipe or a wire to get it to them.”

Designing the Business Model Around Regulatory Arbitrage

Intersect’s entire architecture exploits regulatory gaps rather than fighting through regulatory processes. “We built a business model that is not go right at something. You don’t just hit your head against the wall,” Sheldon said.

The solution: gigawatt-scale power plants in locations with stranded resources, paired with behind-the-meter data centers that never connect to the utility grid. “We actually have essentially developed, it’s almost like real estate development where we develop our own power plants and then we develop sites around them where people with load can come,” Sheldon explained.

Behind-the-meter operation means bypassing state public utility commissions, FERC jurisdictional overlaps, and ISO/RTO coordination failures. The power flows directly from generation to consumption without touching regulated transmission infrastructure.

This extends to technology choices. While policy debates favor nuclear small modular reactors and central-scale combined cycle gas plants, Intersect uses flexible reciprocating engines and aeroderivative turbines—essentially truck engines and jet engines repurposed for power generation—paired with renewables and batteries.

“Wind and solar are in fact the cheapest form of electricity when the wind is blowing and the sun is shining. And if you mix those two together, you take more expensive gas fired generation and put it with those,” Sheldon said. The hybrid approach delivers baseload-equivalent reliability at a fraction of the cost: their model runs substantially below the $120-150 per megawatt hour that nuclear and large gas plants would require, compared to baseline grid prices of $30-40 per megawatt hour.

“The modularity, the flexibility, the redundancy, the cleanness, the cost. It’s the fastest, cheapest, most reliable thing to market,” Sheldon explained. Batteries arrive in shipping containers. Gas generators deploy rapidly. The infrastructure is genuinely modular compared to the 6-8 year timelines and multi-billion dollar capital requirements for new nuclear plants.

The Capital Formation Sequence

Infrastructure at gigawatt scale requires a different capital playbook than B2B SaaS. Intersect starts with hundreds of thousands for land lease options and interconnection queue applications—not to build, but to establish optionality and secure a place in line.

The critical insight: treat contracts as collateral. “You get that contract from the customer and that’s the difference,” Sheldon said. “It’d be like making enterprise software where your first sale was to 10 Fortune 500s and they took everything you could possibly build for the next five years.”

With anchor contracts secured—typically from utilities like the City of Austin or major hyperscalers—Intersect raises billions in non-dilutive project financing. The long-term power purchase agreements become bankable assets that institutional lenders will finance at low cost.

This required building reputation capital first. Sheldon’s track record at Recurrent Energy provided the credibility to secure contracts before having infrastructure operational. “You’re kind of trading on your reputation from what you did last time, because you don’t actually have that plant ready to go, but you’re selling that plant to a customer,” he said.

The scale is staggering. Intersect closed a $900 million equity round at the end of last year. They’ve raised over $2 billion in total equity. This year alone, they’re project financing $9 billion in debt. Next year: another $10 billion.

Optimizing for Project Economics, Not Headcount

Most infrastructure companies scale linearly: double the projects, double the team. Intersect identified which costs are fixed regardless of project size versus which scale with capacity.

“It takes the same number of people in contracts to build a gigawatt plant as it does to build a hundred megawatt plant, so you might as well build the bigger one,” Sheldon explained.

Legal costs, interconnection applications, permitting processes, financing documentation—these are fixed regardless of whether you’re building 100 megawatts or 1,000 megawatts. Construction materials and equipment scale with capacity, but the overhead doesn’t.

The strategy: build only at maximum scale with minimal headcount. This year’s $9 billion buildout spans five to six physical sites. Next year’s $10 billion concentrates on just two locations.

To understand the economics: a single gigawatt data center requires $3-5 billion for on-site power infrastructure, $2.5 billion for the shell, $8-10 billion for turnkey buildout, and $30 billion in chips. “So you’ve got $50 going to $60 billion in one gigawatt,” Sheldon said.

They’re currently building a 600 megawatt site, breaking ground in Q1 2025 on a 1.2 gigawatt site, and negotiating a 3 gigawatt project that could represent $150 billion in total infrastructure when fully built out across secondary phases.

Positioning at the Migrating Constraint

Sheldon analyzes the AI infrastructure stack as a convergence battle. Neo clouds like CoreWeave started at the software layer with Nvidia chip access and are pushing down into owning data centers. Traditional digital infrastructure REITs like Digital Realty and Equinix build colocation facilities but lack power expertise. Utilities understand generation but don’t operate at data center speed or scale.

“For the next decade, there’ll be a constraint in the physical infrastructure,” Sheldon said. “It’ll need cloud providers that have access and expertise to build infrastructure and achieve capital formation around infrastructure.”

That final piece—capital formation expertise for multi-billion dollar physical assets—separates infrastructure builders from infrastructure dreamers. “All of a sudden a bunch of tech companies are going, oh man, this really boring guy who taught project finance at Berkeley, we should talk to him,” Sheldon laughed.

The question is who owns which layers of the stack. CoreWeave and other neo clouds carry software risk—they’re competing directly against Google, Microsoft, and Amazon in cloud services, which makes their valuation multiple vulnerable despite owning hardware. Intersect owns the bottom of the stack where the physics constraint lives, but captures less of the total value.

“It’ll be interesting to watch where it plays out because I do ultimately think that it is the infrastructure that will be the limitation,” Sheldon said.

Unit Economics Over Conference Circuit Narratives

Perhaps the sharpest insight: Sheldon ignores industry consensus in favor of actual delivered unit economics. While energy policy debates favor nuclear SMRs and combined cycle gas plants—driven by lobbying, regulatory capture, and conference circuit repetition—Intersect’s math shows a different optimal solution.

“It’s just math and it’s not hard math,” Sheldon said. “I think actually most people in energy, no matter whether you’re coming from renewables, fossil, nuclear, we can all actually agree it’s some mix of all of it.”

Nuclear plants won’t deliver meaningful capacity for 6-8 years and will run $150+ per megawatt hour when they do. Large combined cycle gas plants require single points of failure that undermine reliability claims and still run $120 per megawatt hour all-in. Intersect’s flexible gas with renewables and batteries delivers faster, cheaper, and with genuine redundancy through modularity.

“These narratives are beginning to take off and you can’t open the paper without reading about how renewables can’t be part of the solution and nukes are the next big thing,” Sheldon said. “It really is ironic because I wish we could just put the politics down.”

The Discipline of Blinders

Despite the media attention and policy debates, Sheldon’s current strategy is radical focus. “I’m just putting my head down and building,” he said. “I’ll invite everybody to see what we built when it’s done.”

The discipline comes from experience. “All that I’ve really seen from the last administration on the Democrats with the haggling over the IRA and renewables and then those going away is that the social commentary on energy understands so little and comes and goes so quickly,” Sheldon explained.

Policy cycles operate on 2-4 year timelines. Infrastructure operates on 20-30 year timelines. The mismatch means builders can’t afford to optimize for current policy incentives.

“None of it invests at the scale or the time horizon of real infrastructure,” Sheldon said. “Those of us who actually build real infrastructure and build these things, these big billion dollar plants in the middle of nowhere, it’s better for us frankly just put our head down and go build it.”

The demand environment enables this focus: “There has never been more demand for electric power. We have never been more in the spotlight. And there is something that is a great relief to really not have to worry about where demand is coming from and just be told, we need you to build and build as fast as you can.”

The Open Question of Independence

Despite Intersect’s multi-billion dollar balance sheet and rapid growth trajectory, Sheldon acknowledges an existential question facing the entire AI infrastructure sector: “How many of what are now relatively nascent companies in that AI infrastructure stack are going to remain independent?”

The AI buildout demands trillion-dollar capital formation. Even well-capitalized infrastructure companies may consolidate into larger players with deeper pockets—sovereign wealth funds, hyperscalers vertically integrating, or utilities finally moving at technology speed.

“The question becomes like, do you want to be there building it all? Do you want to have the front row seat to the infrastructure that redefines humanity or do you want to maximize that small little corner of it that is yours?” Sheldon said.

The trade-off is real: maintain independence and ownership but potentially get outscaled, or join a larger ecosystem and participate in the full buildout while giving up control.

For now, the answer is build. The constraint is real, the demand is unprecedented, and the opportunity to reshape how humanity accesses compute runs through whoever can deliver gigawatt-scale power faster and cheaper than the alternatives.

As Sheldon put it: “I said as a person with a multi billion dollar balance sheet” that even companies at that scale may not remain independent in this market. The physics of AI infrastructure might demand consolidation at scales that make today’s “large” players look small.

That’s the reality of building in steel instead of software: you can’t go viral, you can only compound.