Ready to build your own Founder-Led Growth engine? Book a Strategy Call

Frontlines.io | Where B2B Founders Talk GTM.

Strategic Communications Advisory For Visionary Founders

Actionable

Takeaways

Study the bureaucracy's incentive structures before pitching product value:

John spent years mapping how government procurement actually works rather than leading with product capabilities. The critical insight: in DoD sales, the warfighter (end user) doesn't control purchasing decisions. Success requires understanding each stakeholder's specific mandate and aligning your solution to their organizational incentives, not just operational needs. For civilian agencies like NOAA, the dynamics differ entirely. Founders entering govtech should invest 6-12 months learning procurement mechanics before expecting revenue.

Use government contracts as non-dilutive scaling capital for hardware businesses:

WindBorne secured SBIR grants within six months, then landed their first Air Force data delivery contract through Defense Innovation Unit at the two-and-a-half-year mark. John explicitly treated early grants as equivalent to venture funding but without equity dilution. For companies building physical infrastructure at scale (satellites, hardware networks, manufacturing operations), government contracts provide the runway to reach technical milestones that unlock larger B2B opportunities. This sequencing—government funding first, then B2B products built on that foundation—proves more capital-efficient than attempting to raise massive venture rounds upfront for unproven hardware.

Integrate with legacy systems rather than attempting wholesale replacement:

WindBorne doesn't aim to replace the 1,000 radiosondes launched daily worldwide—they're expanding coverage from the current 15% of Earth (where humans can launch traditional balloons) to 100%. The hardware is revolutionary (weeks of flight versus two hours), but the go-to-market integrates into existing weather agency workflows and feeds into established models like GFS and ECMWF. This approach accelerated adoption because agencies could add WindBorne data without overhauling their entire forecasting infrastructure. The displacement of radiosondes becomes economically inevitable long-term, but only after proving the system at scale. Move fast once adjacent technology validates your thesis: WindBorne wasn't investing in AI-based weather forecasting until Huawei's Pangu Weather paper demonstrated that end-to-end neural weather models could compete with physics-based simulations. Once that validation appeared, John's team moved immediately—adopting the open architecture and expanding it into Weather Mesh before the approach became widely adopted. The lesson isn't to wait for competitors, but to monitor adjacent technological developments and move decisively when validation emerges. They built a top-performing model by being early to a proven approach, not first to an unproven one.

Move fast once adjacent technology validates your thesis:

WindBorne wasn't investing in AI-based weather forecasting until Huawei's Pangu Weather paper demonstrated that end-to-end neural weather models could compete with physics-based simulations. Once that validation appeared, John's team moved immediately—adopting the open architecture and expanding it into Weather Mesh before the approach became widely adopted. The lesson isn't to wait for competitors, but to monitor adjacent technological developments and move decisively when validation emerges. They built a top-performing model by being early to a proven approach, not first to an unproven one.

Hire for mid-level roles and promote based on demonstrated judgment:

John hired Dana from Palantir as a proposal writer, not as a sales executive. He watched her demonstrate strong opinions that consistently proved correct, then promoted her to build and lead the entire public sector growth organization. This internal promotion model worked better than external executive hires because the person already understood WindBorne's technology, customers, and internal culture. For specialized domains like government sales, bringing in experienced operators at individual contributor levels and promoting them as they prove their judgment builds more effective organizations than hiring executives to parachute in.

Conversation

Highlights

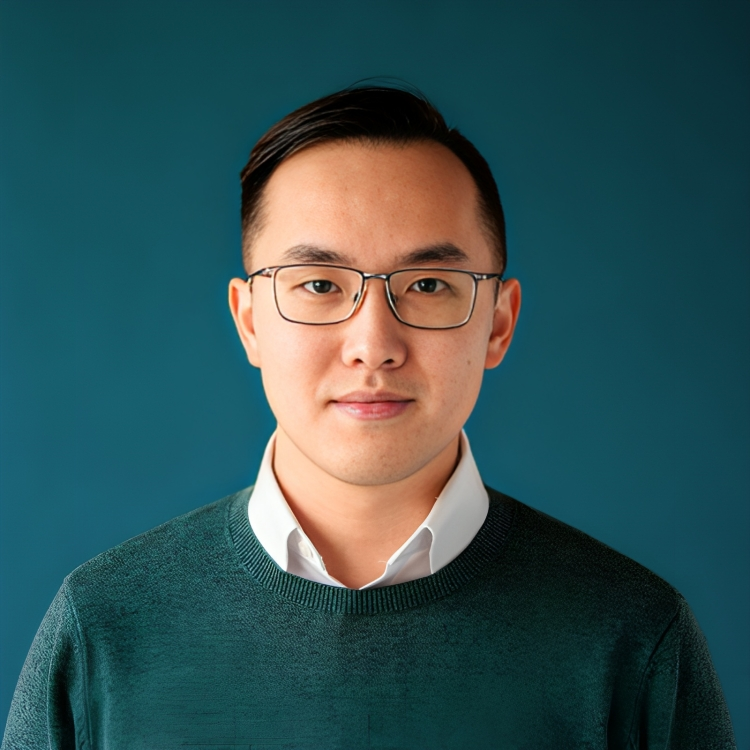

WindBorne Systems: How a Stanford Balloon Project Became a Government Sales Masterclass

Most hardware startups die in the valley between pilot and scale. John Dean found a path that 2019 VCs actively argued against.

In a recent episode of BUILDERS, John Dean, Co-Founder and CEO of WindBorne Systems, explained how his team turned a Stanford Student Space Initiative project into a company flying 100 weather balloons simultaneously—funded primarily by government contracts at gross margins that made B2B expansion viable, not venture capital burned trying to prove a market.

The Technical Genesis

WindBorne wasn’t born from a market gap analysis. John co-led Stanford’s Student Space Initiative, where the constraint was simple: rockets and satellites trigger ITAR controls and require budgets incompatible with student timelines. His co-founder Andre, three years ahead at Stanford, started experimenting with altitude control for weather balloons.

The modification was mechanically straightforward—add a valve to vent helium for descent, add ballast release for ascent. But the operational complexity was substantial. Traditional radiosondes launched by agencies like NOAA fly for two hours, collect a vertical atmospheric profile, then pop. Extending that to week-long flights required solving power management, trajectory prediction, and recovery logistics at scale.

During John’s senior year finals week, they landed a balloon in Morocco. First trans-Atlantic crossing. The team started getting inbound interest from companies wanting payload capacity. But John recognized the real opportunity: “Only 15% of Earth has humans that can launch these traditional weather balloons.” The other 85%—oceans, polar regions, developing nations—represents a massive data gap in global weather modeling.

The Capital Strategy VCs Rejected

After joining PEAR’s accelerator (now PEAR X), John developed a go-to-market thesis that contradicted standard startup sequencing: government contracts first, B2B products later.

His logic was grounded in hardware economics. Building a planetary-scale constellation isn’t capital-constrained in the traditional sense—it’s time-constrained by manufacturing ramp, regulatory approvals, and operational learning curves. “If you want to build a constellation on the size of planet earth with hardware, you have all the money in the world, it still takes time.”

The pitch: “Why dilute yourself as founders with high risk venture capital when you can actually just get paid by government starting first with grants and then with actual revenue to do data services.”

VCs in 2019 pushed back hard. Govtech wasn’t fashionable. They wanted WindBorne to raise large rounds and attack B2B weather forecasting directly. But John understood what they missed: the data moat required years of flight operations to build. Government agencies would pay to help build that moat. The B2B forecasting products could come later, once the infrastructure generated defensible proprietary data.

Mapping Bureaucratic Incentive Structures

WindBorne secured SBIR grants within six months. But John viewed those as equivalent to venture funding—non-dilutive capital without real customer validation. The milestone that mattered came at two and a half years: first data delivery contract with the US Air Force, facilitated through Defense Innovation Unit and the Air Force Lifecycle Management Center.

John navigated the entire process without lobbyists or government sales veterans. His framework: “If you approach government sales with like, oh, I just want to get money, you’re not going to get anywhere because the process is convoluted. But if you approach it with curiosity of like, how does this massive bureaucracy actually work and how does it make decisions, then you will see the path to money.”

He spent years studying procurement mechanics. The critical insight that product-focused founders miss: in Department of Defense sales, “the war fighter is not the purchaser. So the end user, the product doesn’t actually, isn’t actually involved in purchasing system.”

This creates a multi-stakeholder alignment problem. The operational user needs the capability. The program office manages the budget. The procurement office executes the contract. Each has different organizational incentives, risk tolerances, and success metrics. Winning requires mapping all of them, not just proving technical superiority.

WindBorne now maintains roughly 50/50 revenue split between civilian agencies (NOAA, international weather services) and Department of Defense. The dual-market approach de-risks concentration and proves the platform works across different bureaucratic structures.

Integration as Competitive Positioning

WindBorne’s market positioning defies Silicon Valley’s disruption narrative. John is direct about this: “I’m a big believer. I live in the Bay Area, I’m definitely a Silicon Valley kind of like believer. But the idea of like complete disruption just, it wouldn’t make sense in weather.”

The hardware is revolutionary—balloons flying weeks instead of hours, covering regions traditional radiosondes can’t reach. But the go-to-market integrates into existing workflows. WindBorne’s data feeds directly into established operational models like NOAA’s GFS and Europe’s ECMWF.

“My goal isn’t actually to replace traditional weather balloons because traditional weather balloons only cover 15% of the Earth. And my goal is to get to 100%. So you don’t need to see it as like our balloons or other balloons you see as filling gaps that exist now.”

This positioning eliminated the adoption friction that kills most govtech companies. Weather agencies didn’t need to overhaul their forecasting infrastructure or retrain meteorologists. They added a new data source to existing models. The improvement in forecast accuracy justified the contract. The long-term displacement of radiosondes becomes economically inevitable once WindBorne proves the system at 5,000+ balloon scale, but that’s a decade away.

For founders: the “fill gaps in existing systems” positioning accelerates early revenue while building toward structural displacement. The disruption happens, but only after you’ve already captured the market.

Timing the AI Weather Bet

Two and a half years ago, Huawei’s research group published Pangu Weather—the first end-to-end AI weather model competitive with physics-based simulations. Traditional weather models simulate atmospheric physics on CPUs. Pangu Weather used neural networks on GPUs.

John’s team moved within weeks. “We saw the paper come out and this was kind of before there was any news about it. And so we’re like, okay, this is a really interesting paper. We’re going to take that architecture and then kind of expand off of it.”

They built Weather Mesh, which John describes as “a top performing weather model that beats models from like Google, DeepMind and others for weather forecasting.”

The strategic lesson isn’t about being first to AI forecasting—it’s about recognizing when adjacent technology validates your thesis and executing faster than better-funded competitors. WindBorne deliberately avoided AI forecasting investment until someone proved the approach worked. Once Huawei demonstrated viability, WindBorne moved before the approach became consensus and competition intensified.

For technical founders: monitor adjacent breakthrough papers in your domain. When validation appears, you have a 6-12 month window to execute before it becomes table stakes.

The Internal Promotion Playbook

John struggled with founder-led sales transition until he stopped trying to hire external executives.

He brought Dana from Palantir into a proposal writer role. Government contracts require extensive technical proposals—a specialized skill where Palantir experience provided immediate value. But John noticed something more important than her writing: “She was very opinionated about stuff, which is a good sign because the kind of person you want for a leader, for something is going to have strong opinions. And all of her opinions, almost all of them were right as well.”

Instead of hiring a VP of Government Sales to parachute in, John promoted Dana to build and lead WindBorne’s entire public sector growth organization. She already understood the technology, the customer decision-making process, and WindBorne’s operational constraints.

This became John’s repeatable pattern: “I’ve always found it hard to hire like executives to just come in and take over a role. At Wimborne, we very much like promote internally from like, you know, more junior roles into more senior roles.”

For founders in specialized domains (govtech, healthcare, financial services): hiring experienced operators into individual contributor roles and promoting based on demonstrated judgment builds more effective organizations than external executive searches. The person already has context on your product, customers, and culture. You’re validating their judgment in real operational conditions, not inferring it from resume credentials.

Manufacturing as the Constraint

With government sales transitioned to Dana, John refocused on manufacturing scale. WindBorne has maintained 4x annual volume growth for 18 months. They’re flying 100 balloons currently, targeting 500 by end of next year, with an end goal around 10,000 balloons aloft at all times.

The manufacturing challenge isn’t just production volume—it’s maintaining unit economics while scaling. Each balloon needs sensors, communication systems, altitude control mechanisms, and power management. The cost structure has to support both government contracts and future B2B pricing.

John’s 30-year vision extends beyond scaled balloon manufacturing: “Picture millions of little soap bubbles, each one of them with a very tiny chip the size of your fingernail flying all over the world with extremely low environmental footprints telling you about the environment.”

As semiconductor manufacturing improves, sensing and communications could shrink to a single integrated circuit. The trajectory from 100 balloons to millions of fingernail-sized sensors represents the full realization of planetary-scale atmospheric monitoring.

The Playbook

WindBorne’s path offers a replicable framework for hardware companies:

Map incentive structures before optimizing pitch. John spent years understanding how government procurement works—not just who signs contracts, but why each stakeholder cares. In DoD, the end user doesn’t control purchasing. In civilian agencies, budget cycles and inter-agency politics matter more than technical superiority. Map the org chart and incentives before refining your pitch.

Use government contracts as non-dilutive infrastructure capital. For hardware requiring years of buildout before B2B markets become viable, government contracts provide revenue without equity dilution. WindBorne secured grants at six months and contracts at 2.5 years, funding the constellation that later enables B2B forecasting products.

Position as gap-filling, execute as displacement. WindBorne doesn’t claim they’re replacing radiosondes—they’re expanding coverage from 15% to 100% of Earth. This eliminates adoption friction while building toward structural market displacement. The disruption happens after you’ve already captured the market.

Move decisively when adjacent tech validates your thesis. WindBorne didn’t invest in AI forecasting until Pangu Weather proved viability. Then they moved faster than Google and built a competitive model. Monitor breakthrough papers in adjacent domains, then execute in the 6-12 month window before consensus forms.

Hire operators into IC roles, promote on judgment. Dana joined as a proposal writer, demonstrated consistently correct judgment, and now leads public sector growth. For specialized domains, this beats external executive hires who lack context on your product, customers, and operations.

The strategy worked because it aligned with hardware economics. Government contracts funded the infrastructure buildout that unlocks B2B opportunities. For founders building deep tech or hardware, this sequencing—government first, B2B later—might be the only capital-efficient path to scale.