Ready to build your own Founder-Led Growth engine? Book a Strategy Call

Frontlines.io | Where B2B Founders Talk GTM.

Strategic Communications Advisory For Visionary Founders

Actionable

Takeaways

Focus on Complex Problems for Differentiation:

By focusing on high-cost, high-risk patients, Brightside positioned itself as a leader in delivering better care outcomes. Startups can differentiate by tackling the hardest problems within their market.

Leverage Data for Industry Credibility:

Brad used Brightside’s patient data to build credibility with health insurers. Early-stage companies can leverage their data to prove their value and secure partnerships, even before formal pilots.

Strategic Market Entry Through Cash-Pay:

Instead of waiting for insurance partnerships, Brightside started with a cash-pay model to gather data. Founders in regulated industries should consider creative ways to enter the market without waiting for traditional gatekeepers.

Adapt to Regulatory Environments:

Understanding and navigating regulations is crucial in healthcare. Founders must stay ahead of regulatory trends to minimize risk and capitalize on liberalizing rules in sectors like telemedicine.

Build Fast, Learn Faster:

Brad’s team launched Brightside’s alpha in just five months and achieved their first sale within days. Prioritize launching a minimal viable product quickly to test assumptions and learn from real-world feedback.

Conversation

Highlights

How Brightside Cracked Healthcare’s Credibility Trap With 500 Cash Patients and a 30-Page Report

Most healthcare startups die in pilot purgatory. They spend months, sometimes years, trying to convince insurance companies to test their solution. The pilots drag on. Decision-makers change. Requirements shift. Eventually, the startup runs out of runway before proving anything meaningful.

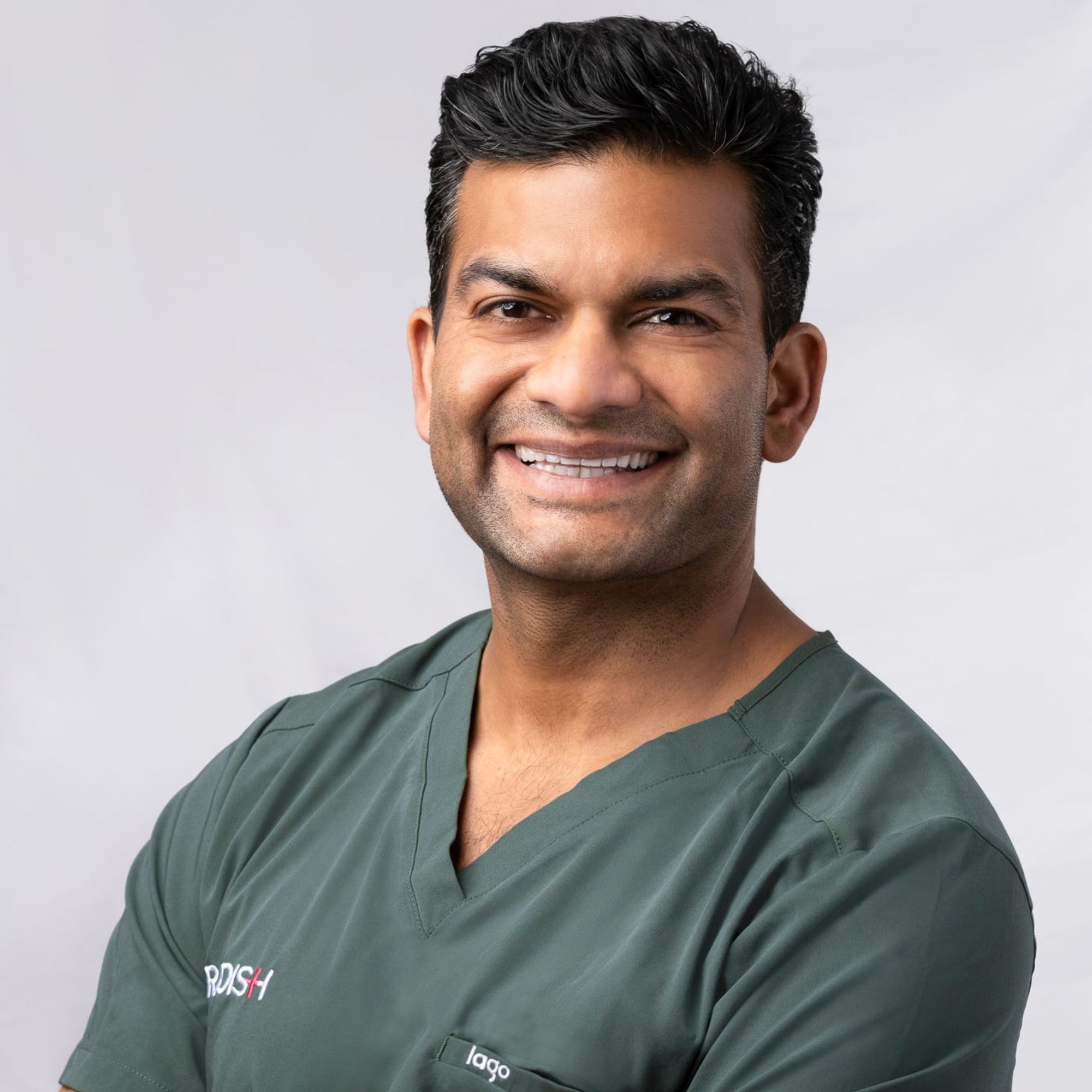

In a recent episode of Category Visionaries, Brad Kittredge, CEO & Co-Founder of Brightside, shared how his virtual mental health platform avoided this fate entirely by turning the traditional healthcare sales cycle on its head. Instead of asking for permission to run a pilot, Brad showed up at Cigna’s door with results from a pilot they didn’t know they were running.

The approach was unconventional, even audacious. But it worked. And it reveals a playbook for how digital health startups can break into insurance networks without getting trapped in the endless loop of pilot programs that rarely convert to real contracts.

The DNA of a Differentiated Thesis

Brad’s journey to founding Brightside didn’t start with a sudden epiphany. It started with pattern recognition. While working with a prominent U.S. health system, he discovered something troubling: “Most of the mental health care that was happening there was happening from primary care doctors. And these primary care doctors were overwhelmed by the demand for mental health care, and that’s really not what they were trained for.”

The structural problems ran deep. The health system had a twelve-week wait for therapy appointments. Getting a psychiatry appointment was nearly impossible unless it was life-or-death. So primary care doctors, with minimal mental health training and short appointment windows, were left to manage complex conditions like depression and anxiety through trial and error.

For Brad, this connected to something deeply personal: “My dad has struggled with depression his whole life. And when he first sought care as an adulthood, from his first encounter to when he finally had some treatment work for him was about a ten year gap, because he fell through the cracks with referrals and follow ups and failed medication trials.”

But personal connection alone doesn’t build a venture-scale company. Brad needed a thesis that was both differentiated and defensible. As he refined his thinking, he realized the industry was making a fundamental mistake: “Everyone talking about access, we’re sort of treating mental health care as a commodity, acting we just need more appointments, and if we have more appointments, we’ll solve this problem.”

His insight cut against conventional wisdom: “If we take that same crappy care that I saw at a great health system and move it online, we’re not solving the problem. What we need is to use this transition from traditional care to virtual care as an opportunity to remake them all from the ground up.”

This became Brightside’s founding principle: build a care model that addresses root quality issues, not just access. It was a harder problem to solve, but it created real differentiation in a market that was starting to get crowded.

Five Months From Code to Revenue

With a clear thesis and his technical co-founder Jeremy Barth on board, Brad faced a critical question: what did they need to prove first? The market was skeptical. This was 2017, pre-pandemic, when telemedicine adoption was in the single digits and mental health still carried significant stigma.

Brad remembers the skepticism clearly: “I had been trying to pitch it in parallel and a lot of people said, I don’t know if consumers are going to be comfortable with that. I don’t think someone would choose to like see a doctor online that way.”

So that became the hypothesis to test: would consumers actually use remote mental health care? Jeremy started writing code in September 2017. They launched their alpha in January 2018. Within a week, they had their first revenue.

The moment was validating: “Within two days of maybe putting up our site with no ad spend or maybe $100 of ad spend, we got our first purchase. And so Jeremy got a text message on his phone with the stripe verification of a charge and he kept that screenshot. And the feeling that we had when that happened was like, oh man, this is real. This is going to work.”

The Credibility Trap

Proving consumer demand was one thing. Getting insurance companies to work with them was another entirely. Brad describes the challenge: “Starting a healthcare company, another reason that it’s hard is that obviously most people want to pay with their insurance for any health care that they get. When you’re starting as like a digital health startup, you have so such little credibility with any sort of traditional healthcare stakeholder, including the health insurance companies.”

This is the credibility trap that kills most digital health companies. Payers won’t contract with you until you have proof. But you can’t get proof without being in network. The traditional solution—pilot programs—often just delays the inevitable.

Brad chose a different path: “We decided that the strategy we might take is to start by accepting cash and that we can get customers that way, and that the way to build credibility was going to be with data. Instead of just going and telling people what we can do, let’s go show them with the data.”

The execution was surgical. Even though Brightside was charging cash, they collected insurance information from every customer. When they had 500 members with Cigna insurance who had been customers for at least three months, they made their move.

“We analyzed all the data and turned it into like a 30 page report with a bunch of, you know, charts and takeaways and insights. And then I just went knocking on every door I could find at Cigna and tried to get intros and finally found an audience.”

The positioning was brilliant: “Here are the results of the pilot you guys didn’t know you were doing with us. Because a lot of healthcare companies get stuck in pilot purgatory. And I didn’t want them to even suggest that’s how we start together.”

This wasn’t just clever messaging. It was a complete reframe of the conversation. Instead of asking “will you pilot with us?”—a question that puts all the power in the payer’s hands—Brad was saying “here’s what we’ve already proven with your members.” It demonstrated demand, showed outcomes, and proved operational readiness all at once.

The result: a national contract with Cigna while Brightside was still a small startup.

The Unit Economics Bet

The move to insurance wasn’t just about market size. Brad had a specific thesis about unit economics: “More people are going to want to pay with their insurance. And when you think about the value proposition, if you’re going to get healthcare, whether you’re going to pay out of pocket or pay with your insurance, obviously your out of pocket cost is just way lower with your insurance.”

This translated directly to acquisition economics: “That translates back into this assumption or thesis that we could acquire those customers for a much lower acquisition costs, that our CAC would be much lower, and that our CAC to LTV ratio would be much more attractive inside the insurance networks rather than cash outside.”

The thesis proved out: “We have dramatically lower acquisition costs because of the value proposition when we can accept someone’s insurance, we have a great LTV with insurance and great unit economics and revenue dynamics.”

Planting a Flag in the Hard Cases

As Brightside scaled and competitors flooded the market, Brad faced a new challenge: differentiation. “We still found when were going to talk to payers and that we had many other competitors enter the market in that interim, that people were having a hard time telling us apart from everybody else, saying, like, everybody talks about quality, everybody says they’re great and that they can offer more access.”

The solution came from following the money. Brad recognized that in healthcare, cost distribution is highly uneven: “You’ve got a small portion of people that have more complex, severe, or acute conditions driving a massively disproportionate share of the total costs of that population.”

This led to a critical strategic decision: build a crisis care program for suicide prevention. It was exactly the type of program competitors were avoiding. As one suicide advocacy executive told Brad about high-risk patients: “Those patients are a hot potato. No one wants to take them because no one’s trained specifically, or very few providers are trained specifically to treat suicidality.”

Brad saw opportunity where others saw risk: “To me, that was just really planting a flag, saying, we are going to be the best at treating the hardest cases. We’re not going to shy away. We’re going to do the hard work. And that’s how we’re going to differentiate from everybody else in the market.”

The competitive moat was clear: “I don’t think anybody else has the DNA to want to follow us in doing this and doing this really hard work and impactful work.”

The Playbook

Today, Brightside serves 135 million covered lives across commercial insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, and healthcare exchanges. The journey from that first Stripe notification to a comprehensive mental health platform offers a blueprint for healthcare founders facing similar challenges.

The lesson isn’t about clever tactics. It’s about strategic positioning at every stage. Start with a genuinely differentiated thesis—don’t just move existing care online. Identify what you need to prove first and build the minimum to prove it fast. Use cash customers to build data assets that prove value to payers. Present findings as fait accompli, not requests for pilots. And when competition intensifies, double down on the hardest problems that create the most value.

As Brad puts it, the vision has always been to “fundamentally change the quality of care that people receive for mental health conditions in the US. Certainly that involves timely access to care and a great experience with care. But in many ways, it really means changing mental health care from art to science.”

That’s the real insight: the companies that win in healthcare aren’t the ones that make incremental improvements. They’re the ones willing to do the hard work of fundamentally remaking care delivery—and finding clever ways to prove it works before anyone asks them to.