Ready to build your own Founder-Led Growth engine? Book a Strategy Call

Frontlines.io | Where B2B Founders Talk GTM.

Strategic Communications Advisory For Visionary Founders

Actionable

Takeaways

Start Small, Think Big:

Epitel’s early focus was on a single use case—seizure detection—but they have a long-term vision for addressing broader brain health issues. Founders should focus on solving a specific problem first, then expand into adjacent areas.

Strategic Funding Decisions:

Instead of following traditional startup funding advice, Mark leveraged NIH grants to de-risk the development process. For founders in regulated industries, non-dilutive funding can be a critical bridge before taking on institutional investment.

Build Investor Relationships Early:

Mark emphasized the importance of finding investors who understand the long-term nature of medtech development. Founders should seek investors who have experience with similar time horizons and regulatory challenges.

Leverage AI for Efficiency, Not Replacement:

Epitel’s AI doesn’t replace neurologists but instead makes their work more efficient by flagging potential seizure events in long-term data. Founders working with AI should focus on how it enhances human expertise rather than positioning it as a replacement.

Stay Focused on the End User:

Mark highlighted how making the product easy for patients to use—no goopy gels or complicated equipment—is central to their success. Founders should prioritize user experience, especially in industries like healthcare where patient compliance can impact outcomes.

Conversation

Highlights

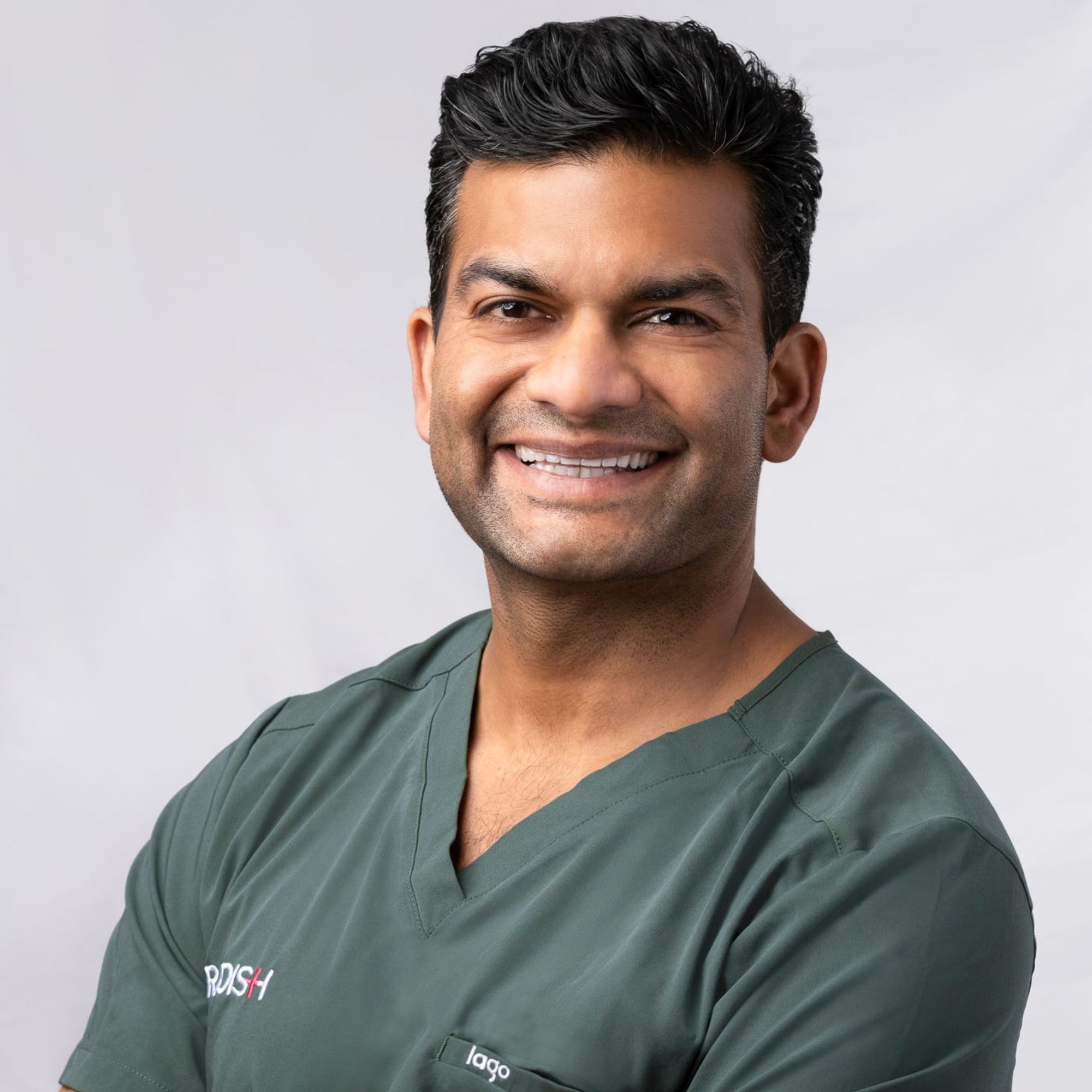

When Your Seed Round Takes 15 Years: Building Epitel on Government Grants

Most founders obsess over their first VC check. Mark Lehmkuhle spent 15 years avoiding it.

In a recent episode of Category Visionaries, Mark Lehmkuhle, CEO and Founder of Epitel, a brain health technology platform that’s raised over $20 million, shared a go-to-market journey that defies conventional startup wisdom. While the tech world celebrates speed and scale, Mark’s path to commercialization required patience, government grants, and an artist colony with broken heating.

The story isn’t just unusual—it reveals fundamental truths about building in regulated industries that most founders never confront until it’s too late.

The Pivot That Wasn’t

Mark’s journey began in 2008 at the University of Utah, where he identified a striking parallel between neurology and cardiology. “Right now, you could walk into your neighborhood clinic and walk out with a wireless halter monitor for your heart,” Mark explains. “But your chances of getting a long term EEG anywhere, even if you go to your neighborhood hospital, is slim to none.”

This wasn’t a minor market inefficiency—it was a fundamental infrastructure gap. Seizures affect one in ten people during their lifetime, yet the diagnostic technology remained tethered to 1980s-era equipment. The gold standard was a three-day wired EEG where patients “got a wrap of gauze around your head. It’s coming down to an old school recorder that looks like a vhs tape deck, and you got to wear that for three days. And you can’t shower or anything like that.”

Unlike typical startup pivots, Epitel’s founding insight remained constant for 15 years. The challenge wasn’t finding product-market fit—it was surviving long enough to reach the market at all.

The Grant Funding Gauntlet

Most medical device founders see grants as supplementary funding. Mark made them the entire strategy. Through the NIH’s Small Business Innovative Research (SBIR) program, Epitel developed their wireless EEG sensor and navigated FDA clearance without dilution.

The trade-off was brutal. “These grants aren’t very big, and they take a long time to develop anything on them,” Mark acknowledges. For years, he split time between the university and a company housed “literally in an artist colony because that’s the only thing that we could afford. So we’re building medical devices in an art studio in the heat of—the heat doesn’t work very well. The air conditioning didn’t work at all.”

The grant process itself forced discipline that fast money might have obscured. “It really, as a Founder, allows you to dig in and really think about what you’re developing. You know, who are you developing it for? Why are you developing it? What’s the value proposition? The whole package.”

But the grants created an unexpected bottleneck that revealed just how different medical AI is from consumer AI.

The Dataset Nobody Would Sell

When Epitel needed training data for their machine learning algorithm, Mark looked to cardiology for guidance. The answer seemed straightforward: “We just purchased 30,000 EKG records that were well annotated.”

Epitel approached hospitals with epilepsy monitoring units with the same request. The response was devastating: “No, we don’t have the storage for that. You know, after we record it, we enter the report into the electronic health record, and then we just delete the data because we don’t have the storage for it.”

This wasn’t a procurement problem—it was an infrastructure problem that would add years to development. “So now we’re going to have to develop our own data set,” Mark realized. The company spent years collecting data where “we used the wired EEG as kind of the ground truth and then trained our machine learning on our sensor data.”

In hindsight, this forced data collection created an unintended moat. Any competitor would face the same multi-year challenge, unable to buy or scrape their way to a competing algorithm in a regulated medical device market.

From Four Engineers to FDA Clearance

The regulatory path added another layer of complexity to the go-to-market timeline. “From a regulatory perspective, we’re still regulated by the FDA, but we’re kind of on the lower end of their regulatory spectrum, something that’s called a predicate 510,” Mark explains.

For investors to take Epitel seriously, the team needed to prove regulatory competency before fundraising. “We kind of really needed to get this product through the FDA to show these institutional investors that we could do something like this, because, again, were four engineers. None of us had ever commercialized anything ever before.”

This creates a chicken-and-egg problem unique to medical devices: you need funding to develop the product, but you need regulatory clearance to attract serious funding. Grants solved this paradox, allowing Epitel to build credibility without burning investor capital on a team that had never shipped anything.

The $20 Million Reality Check

After years of grant funding, Mark faced bad advice at the fundraising stage. “At the time when were grant funded, I would say that were getting a lot of bad advice of, oh, you should go through, you know, kind of seed stage investors, seed stage investors, when really our NIH grants were that seed stage for us.”

The company ultimately raised over $20 million in their Series A—a significant jump that required finding investors who understood medical device timelines. “Any seed stage investor is just not going to see the return on that investment for a long period of time. So it really took our board members to make these warm introductions to the type of investor that can see that long game and has the wherewithal to be able to do that.”

Interestingly, one lead investor was “primarily a biotech investor that I’m pretty sure were their first medtech investment,” demonstrating that experience with long development cycles mattered more than narrow sector focus.

Four Weeks Into the Real Test

Fifteen years after founding, Epitel launched commercially four weeks before this conversation. For Mark, who spent his career in R&D, commercialization represents an entirely new challenge.

“We need to demonstrate that doctors want it, they’re buying it, they’re getting reimbursed for it through traditional channels, and they’re rebuying it,” Mark explains. The reorder metric is particularly crucial—it proves patients tolerate the device and results are clinically useful.

The company is deliberately focusing on two geographic markets to prove the model before scaling. “Here’s what we can do in two geographical locations with these very limited resources. Now we’re fundraising again for our series B, what we’re calling our series B, to really then scale this nationally.”

Mark’s honest about his learning curve: “It’s something I’ve never done before is sell anything. So it’s, you know, we hire the team. We’ve got a very limited team because we’re only on our series a at the moment. But it’s super exciting and also really scary because I’ve never commercialized anything before.”

Selling to Multiple Stakeholder Maps

Epitel’s GTM complexity stems from serving two distinct use cases with different buying processes. In outpatient settings, “we’re selling directly to the neurologist” through a prescription model. But in hospitals, “if it’s the emergency department, docs, their nurses, ultimately a neurologist is involved who’s reviewing the data. We need to show the value proposition to the hospital itself. So it’s a little bit, there’s more stakeholders for sure on the hospital side.”

The AI component adds another layer to the sales conversation. When physicians worry about replacement, Mark reframes the technology: “Instead of spending, in our case, hours and hours reviewing EEG data where nothing’s going on, let use the AI to identify those events that you should be looking at, and then you’ll spend more time with your patients rather than reviewing this EEG.”

The regulatory framework actually helps the sales story. “We’re a regulated industry. It’s a medical device, and we have to submit these, any changes that we make to the FDA. So it’s not like we’re going rogue and creating this monster that’s going to take over and tell you that you have this disease or that disease.”

The Long Game Continues

Mark’s vision extends far beyond seizure detection into comprehensive brain health monitoring. “Could we detect the symptoms of Alzheimer’s through eeg years before you have any physical symptoms? And in that way, we could have an intervention early on that either slows the progression or even prevents the disease altogether.”

When asked for advice on pursuing grants, Mark’s answer captures the entire journey: “To stick with it. If you truly think you have something innovative, all it takes is time. If you’re willing to put in the time, stick with it, you’ll get there.”

For founders building in regulated industries, Epitel’s story reveals an uncomfortable reality: some innovations can’t be rushed, and sometimes the slower path preserves both equity and focus in ways that matter long-term. The question isn’t whether grants are better than VC—it’s whether your innovation, market, and personal situation can survive a 15-year build to commercialization.

Mark proved it’s possible. The test now is whether the commercial execution can match the technical achievement.