Ready to build your own Founder-Led Growth engine? Book a Strategy Call

Frontlines.io | Where B2B Founders Talk GTM.

Strategic Communications Advisory For Visionary Founders

Actionable

Takeaways

Discovery trumps differentiation in category creation:

Confirm's design partner had promoted toxic employees and lost quiet high performers in the same cycle - a perfect case study for their ONA methodology. But when they pitched other HR leaders with "here's why your approach is broken," they hit walls. The shift: stop selling methodology, start diagnosing pain. Reference what you've observed at similar companies—"Some folks at your size tell us they struggle with X, is that true for you?"—then let prospects surface their version of the problem. Only after they've articulated their pain do you map your differentiated approach to their specific context.

Target buyer timing, not just buyer titles:

Confirm identified a specific trigger: HR leaders in their first 1-2 months at a new company. These leaders are hired to make change and need early wins. The outreach question: "How are you looking to make your mark?" This surfaces whether they're hungry for innovation or managing political capital. A newly hired CHRO has different motivations than a 5-year veteran protecting their process choices. Map your outreach to career timing, not just seniority.

Enforce 50/30/20 talk ratios in discovery:

David's target: prospects speak 60-80% of discovery calls, with 50% being acceptable. If you're talking more than half the time, you're pitching, not discovering. The clinical psychology technique: positive encouragers ("yeah," "huh") plus deliberate silence after open-ended questions. Prospects will fill silence with the real issues—budget constraints, political dynamics, past vendor failures. This intel is gold for multi-threading and objection handling later.

Test channel-message fit with minimal spend:

Confirm's approach: "do everything a little bit and see what sticks." They found LinkedIn ads with precise targeting (title, company size, recent job changes) delivered qualified pipeline cost-effectively, while other channels didn't. The framework: allocate 10-15% of budget across 5-6 channels for 60 days, measure cost-per-qualified-meeting, then concentrate spend. Plan for 3-6 month creative refresh cycles as audiences develop ad fatigue—this isn't set-and-forget

Map your product to the HR buying matrix:

David identifies four distinct quadrants: (1) CHRO buyer, company-wide deployment = traditional enterprise sale, 6-18 month cycles, heavy multi-threading required; (2) CHRO buyer, HR-only tool = shorter cycles but still executive selling; (3) Line manager buyer, company-wide = requires bottom-up adoption mechanics; (4) Line manager buyer, HR-only = SMB-style transactional sale. Confirm operates in quadrant 1—the longest, most complex sale. Most founders don't explicitly map which quadrant they're in, leading to mismatched sales motions and blown forecasts.

Use provocative messaging with technical substance:

"One-click performance reviews" generated meetings because it triggered both excitement (managers hate writing reviews) and concern (is AI replacing human judgment?). The key: the shock factor gets the meeting, but you need depth on the call. Confirm's explanation: the AI aggregates data from Asana, Jira, OKRs, peer feedback, and self-reflections to reduce recency bias, then generates a draft managers edit. The dystopian concern becomes a feature when you explain the data anchoring. Surface-level shock without technical credibility burns trust.

Adjust for organizational risk tolerance by function:

HR and healthcare share conservative buying cultures due to compliance, documentation, and legal requirements. David contrasts this with selling to CTOs or engineers who "kick tires and want to break things." This affects everything: longer evaluation cycles, more stakeholders in legal/compliance, emphasis on security and data handling, reference checks weighted heavily. If you're selling to risk-averse functions, adjust your content (white papers, compliance documentation), your timeline expectations, and your change management positioning.

Reframe education as extraction, not instruction:

David's mental model shift: "I need to learn from them" replaced "I need to educate them." In practice: "I've heard from others that calibration meetings consume 10+ hours per cycle with unclear outcomes. They tried approaches like forced ranking or manager-only decisions. Have you experimented with either?" This positions you as a pattern-matcher across their peer group, not a lecturer. They become receptive to alternatives because you've demonstrated you understand their world through other customers' experiences.

Conversation

Highlights

Why Leading with Methodology Superiority Kills Category Creation Deals

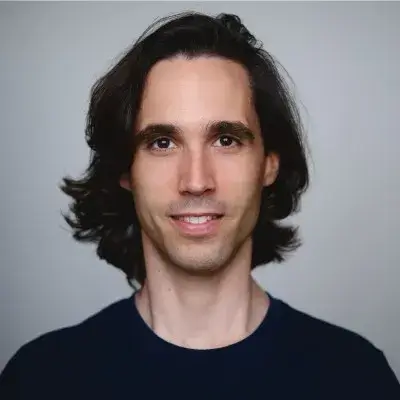

David Murray spent months watching qualified prospects ghost Confirm after discovery calls. The pattern was consistent: HR leaders would listen politely to his pitch about organizational network analysis, ask thoughtful questions, then disappear.

The problem wasn’t the methodology. Confirm’s approach actually worked—their design partner had just promoted employees who became so toxic they were managed out days later, while critical contributors left unrecognized. Confirm’s network analysis surfaced both issues immediately by asking employees simple questions: Who do you go to for help? Who energizes you? Who’s outstanding around you?

But when David pitched other HR leaders with “here’s why traditional performance reviews are broken and here’s our better approach,” deals died.

In a recent episode of BUILDERS, David, Cofounder & CEO of Confirm, shared the specific pivot that transformed their enterprise sales motion—and why discovery-based selling matters more than methodology superiority when creating new categories.

The $0 Return on Methodology-First Positioning

Confirm had proof their approach worked. Their design partner—a 1,000+ person organization—suffered from the exact problems traditional performance reviews create: popularity contests, manager bias (research by Maynard Goff shows 60% of ratings reflect manager idiosyncrasies rather than actual performance), and complete visibility gaps on quiet high performers.

After one cycle with Confirm’s organizational network analysis, the talent surprises were dramatic. The methodology identified introverted contributors everyone relied on but managers didn’t know about, plus toxic performers skilled at managing up.

David’s team assumed this would resonate with every HR leader. They were wrong.

“The big mistake that we made in our early days trying to sell this thing was we basically kind of said, hey, let’s reinvent your performance review system from scratch,” David explains. “It was trying to like climb a mountain on skis uphill. And it’s because if you try to like come in as, like, I know more than you. Especially because, like, we’re tech people—definitely people were telling us to pounce down in a very respectful way. They just ghost us.”

The failure wasn’t about product-market fit. It was positioning: telling prospects their approach was broken triggered defensiveness, not interest.

“This was actually the hardest go to market lesson for us to learn in our early days, which is if you tell people that what they’re doing is wrong, then they’ll say pound sand.”

The Discovery-First Framework That Fixed Win Rates

The pivot required abandoning their entire pitch structure. Instead of leading with methodology, Confirm started with pure problem discovery.

“What we learned the hard way is you have to meet people where they are,” David says. “You got to do discovery based off of the problems that they’re trying to solve. And in particular for the HR audiences that we talk to a lot of them, it’s philosophy first, tools second.”

The new framework: identify what’s working, what isn’t, and which problems prospects actually acknowledge—then inject only the parts of your solution relevant to their articulated pain.

“If you have a solution to a problem they have not surfaced, don’t pretend that they have that problem,” David explains. The alternative: reference what similar companies experience as a hypothesis, not a prescription. “Some of the other folks that we talk to at your size and stage tell us that they have problem xyz, is that a problem for you? And if they say, no, don’t fight it.”

Only after prospects surface their specific pain points does Confirm map their organizational network analysis methodology to solving those problems. The methodology becomes the answer to their question, not your opening statement.

The 60/40 Talk Ratio That Surfaces Real Buying Triggers

David enforces specific talk ratios on discovery calls, drawing from clinical psychology training: prospects should speak 60-80% of the conversation, with 50% being the minimum acceptable threshold.

“If you’re doing more than half the talking, especially in that first discovery call, you’re doing something wrong.”

The technique: positive encouragers (“yeah,” “huh”) plus open-ended questions that can’t be answered with yes/no. The critical skill: sitting with silence after asking questions.

“Be willing to sit with silence and you’ll find that people will fill the space,” David says. “I’ve heard from a lot of great negotiators sometimes that’s the best thing that you can do in a negotiation as well.”

Prospects filling silence reveal the actual issues: budget constraints, political dynamics, past vendor failures, internal resistance to change. This intelligence directly informs multi-threading strategy and objection handling in later stages.

For technical founders who default to solution-oriented thinking, enforcing this ratio requires conscious discipline. “My background is I’m an engineer, like product person. As an engineer and just a tech person, I always led with like the solution, the technology, why it’s better,” David admits.

The mental shift: you’re actually lower than prospects from a knowledge standpoint in discovery. “You know nothing about the person’s life that you’re talking to, the job that they’re in, like what they’re trying to accomplish. Only they can tell you that.”

Targeting Career Timing as a Buying Signal

Not all HR leaders have the same risk tolerance or change appetite. Confirm identified a specific trigger: HR leaders in their first 1-2 months at new companies.

“One of our go to market strategies was to look at folks that have recently started in a senior leadership role on LinkedIn and then have outreach after their first month or two to just say, like, how are you looking to make your mark?”

Newly hired CHROs are brought in to innovate and need early wins. Five-year veterans are protecting existing process investments and managing political capital differently.

“You got to find what people actually care about and what motivates them,” David explains. “For some people, actually change could actually be really great. Like, for example, if someone’s new in a role who’s been hired to shake things up and to be an innovator and to do new things, those folks might be super interested in what you’re doing.”

The LinkedIn filter: recent job changes at target companies, then outreach timed to their window of maximum change appetite and minimal political baggage.

The Four-Quadrant Framework for Segmenting HR Sales

Confirm mapped HR buying motions into four distinct quadrants based on two variables: buyer level (CHRO/VP vs. line manager) and deployment scope (company-wide vs. HR team only).

Each quadrant requires completely different sales approaches:

Quadrant 1 (CHRO + company-wide): Traditional mid-market to enterprise sale. “In our case we kind of had the most challenging quadrant which is selling into like CHRO and VPs of performance and we need all your whole company on this thing. That sale is where you got to do a lot of multi threading.” Sales cycles: 6-18 months for 500-10,000 employee organizations. Heavy emphasis on white papers, content, security documentation, legal review.

Quadrant 2 (CHRO + HR-only): Still executive selling but shorter cycles since deployment is contained.

Quadrant 3 (Line manager + company-wide): Requires bottom-up adoption mechanics and different stakeholder management.

Quadrant 4 (Line manager + HR-only): SMB-style transactional sale with faster close velocity.

Most founders don’t explicitly map which quadrant they’re in, leading to mismatched sales motions and blown forecast accuracy. A line manager tool sold with enterprise motion wastes resources; a CHRO tool sold with SMB velocity under-resources deals.

Reframing Education as Extraction

The most counterintuitive shift: reconceptualizing what “education sales” means when creating categories.

“The biggest flip for me was thinking about an education sale as I need to come in and educate them. But flipping this on its head to an education sale is about I need to come and learn from them, learn from where they’re successful, where are they failing and why, where are they struggling and why.”

In practice: “I’ve heard X, Y and Z from person A, B and C. They tried Q, R and S. Have you tried that before? Are you familiar with that before? And then that can leave kind of that conversation open where then actually they’ll be receptive to what you have to say.”

This positions you as a pattern-matcher across peer companies rather than a lecturer. Prospects become receptive to alternatives because you’ve demonstrated you understand their context through aggregated customer experience, not because you’ve told them they’re wrong.

The education happens after extraction, not instead of it. And it’s framed as options other similar companies tried, not prescriptions you’re imposing.

Adjusting for Organizational Risk Tolerance

HR shares characteristics with other conservative buying functions like healthcare and legal: compliance requirements, documentation needs, and career risk from vendor failures.

“Audiences where folks are typically coming from a background where they’ve been working in HR—just by its nature, it needs to be conservative. Legal things matter, documentation matters,” David explains. “Being really innovative and shaking things up, it’s just something you got to be really sensitive to. And it’s very different than selling to a CTO or even an engineer, where they may be very quick to kick tires and want to break things.”

This affects everything: evaluation timeline expectations (longer), stakeholder composition (legal, compliance, security all involved), content requirements (white papers, security documentation heavily weighted), and reference check emphasis (past vendor performance matters more than feature innovation).

If you’re selling to risk-averse functions, match your positioning to their organizational reality. Change management framing, incremental rollout options, and compliance documentation aren’t nice-to-haves—they’re table stakes.

The Implementation Discipline

For technical founders building category-creating products, the lesson isn’t “be nicer in sales calls.” It’s enforcing process discipline that contradicts your instincts.

Your methodology might be superior. Your technology might solve real problems. But leading with that superiority kills deals because it positions prospects as having made poor decisions—decisions they own and defend.

The alternative: discovery that genuinely learns from prospects, extracts their specific pain, then maps your differentiated approach to problems they’ve already articulated in their own words.

As David puts it: “If you tell people that what they’re doing is wrong, then they’ll say pound sand.”

The category creation paradox: you’re selling something new, but you can’t lead by telling people the old way is broken. You have to let them tell you what’s broken, then offer your new approach as the solution to their articulated problem.