Ready to build your own Founder-Led Growth engine? Book a Strategy Call

Frontlines.io | Where B2B Founders Talk GTM.

Strategic Communications Advisory For Visionary Founders

Actionable

Takeaways

Match your narrative precision to technical depth:

CoreStory deploys three distinct positioning strategies based on audience sophistication. For AI practitioners tracking benchmarks, they lead with "44% SWE-bench improvement"—a metric that immediately signals meaningful progress on the hardest problem in the space. For engineering leaders aware of AI tooling but not deep in the research, they focus on velocity gains and ROI metrics. For executives, they describe reverse-engineering codebases into machine-readable specs. The key insight: technical audiences dismiss vague value props, while non-technical audiences get lost in benchmark details. Map your positioning to how your audience measures success in their world.

Seed category language through earned adoption, not manufactured consensus:

Anand initially called their approach "requirements-driven development" before simplifying to "spec-driven development." Rather than pitching analysts, they used the term consistently in customer conversations, gave talks at GitHub Universe, and shipped demos showing the workflow. When customers naturally adopted the language and community leaders began using similar terminology independently, Microsoft and GitHub followed with their own implementations (like GitHub's SpecKit). The lesson: category language sticks when practitioners choose to use it because it clarifies their work, not because a vendor pushed it. Focus on customer adoption as proof of concept before seeking broader market validation.

Position against emergent practices, not just incumbent products:

CoreStory doesn't position against legacy code analysis tools—they position as the enabler of AI-native engineering, the discipline that will displace Agile. Anand's insight from watching JIRA's success: "People don't love JIRA. What they love is Agile as a way to move away from waterfall." CoreStory is betting that 10x velocity gains from AI-native practices will drive the same categorical shift. When you're early in a technology wave, attach to the practice change (how teams will work differently) rather than feature comparisons with existing tools. Movements create markets.

Design channel strategy around customer problem awareness:

CoreStory's three channels map to different stages of buyer sophistication. Direct enterprise comes from teams already deep in AI engineering who've hit the context limitation wall. Coding agent partnerships (via MCP integration with tools like Cognition and Factory) serve builders wanting better AI tooling who haven't diagnosed the context problem yet. Hyperscalers and GSIs distribute into modernization and maintenance projects where AI enablement is emerging as a requirement. Each channel serves a distinct buyer journey stage. Don't force one go-to-market motion—design multiple paths based on where different customer segments are in understanding the problem you solve.

Navigate pre-legitimacy markets by hiding the breakthrough:

Before ChatGPT, selling anything AI-driven faced immediate skepticism about whether it was "real" or just smoke and mirrors. Anand couldn't lead with AI without triggering disbelief. CoreStory focused on delivered outcomes—"here's what you'll be able to do"—with AI as the mechanism, not the message. Post-ChatGPT, the challenge flipped: everyone expects AI, but now the differentiation question becomes harder. If you're building on emerging technology before market consensus forms, deemphasize the technology until buyers have context to evaluate it. Once the market validates the technology category, shift to demonstrating your specific technical advantage within it.

Conversation

Highlights

How CoreStory Seeded “Spec-Driven Development” Across Microsoft and GitHub Without Analyst Relations

Eighteen months before ChatGPT launched, Anand Kulkarni was already building on the GPT-3 API. While most of the market dismissed AI as vaporware, CoreStory was discovering a fundamental limitation that persists even in today’s most advanced models: coding agents fail at real-world engineering tasks in complex enterprise codebases.

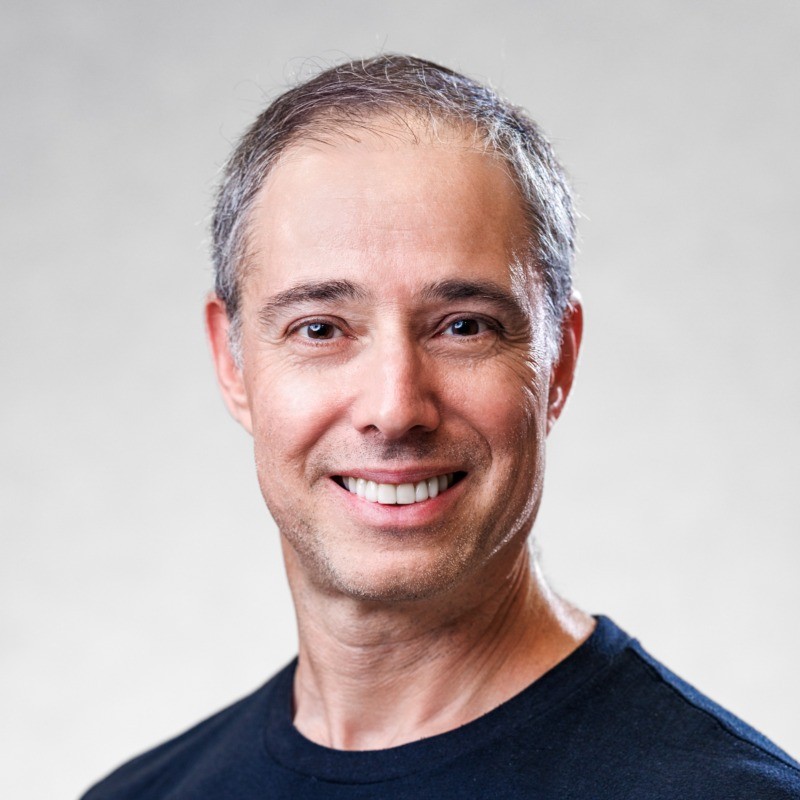

In a recent episode of BUILDERS, Anand, CEO of CoreStory, explained how his code intelligence platform achieved a 44% improvement on SWE-bench—the industry’s standard benchmark for coding agent performance—and more importantly, how he seeded category language that Microsoft, GitHub, and Amazon now use without ever touching Gartner.

The Context Problem Everyone Missed

While foundation model companies celebrated coding agents as the future of software development, Anand identified a problem hiding in the benchmarks themselves.

“Coding agents are very good at writing code, and they’re pretty good at reading code in small chunks,” Anand explained. “The places where coding agents really struggle is in what we’d consider to be really big, complicated enterprise code bases, right? The kinds of things that span 10, 20, 30 million lines of code or might have lots of complex interdependencies.”

SWE-bench exposes this limitation clearly. The benchmark uses real-world GitHub issues from repositories like Django and asks coding agents to fix actual bugs. “Even here at GPT 5 levels and Opus 4.5 levels, none of these guys can really pass those benchmarks,” Anand noted. “Even if they’re included in the training sets. They struggle.”

CoreStory’s thesis: coding agents don’t need better language models—they need an intelligence layer that provides context about how complex systems actually work. “You can make those agents smarter more by giving it additional context,” Anand explained. “We provide an intelligence model on top of code. I think the term of art that people are using right now is a context agent.”

The result is quantifiable: “It improves how these coding agents do on the SUI benchmark by about 44%, which, if you’re an insider, is a huge gain in how smart these things are when they are able to consult Core Story.”

Navigating Pre-Legitimacy Markets by Repositioning the Breakthrough

Before ChatGPT, leading with AI triggered immediate skepticism. Anand couldn’t position CoreStory as an AI company without buyers assuming it was fraudulent.

“You actually could not really position yourself as AI in the sense that you are required to do today,” Anand recalled. “You couldn’t really be totally upfront about that, or people would simply respond with disbelief. They would suggest that, okay, it’s smoke and mirrors, it’s not really AI. There’s some human beings under the hood and there’s some magic you’re doing here that you’re not telling us.”

CoreStory’s pre-ChatGPT positioning focused on delivered outcomes with AI as the mechanism, not the message. They described what engineering teams could accomplish without emphasizing how the technology worked.

The ChatGPT moment flipped the challenge entirely. “The shift here is now that there’s an expectation that, yeah, it is AI, and there is a real need, probably a demand from entities on the other end to use AI to do this, especially technical leaders in the market.”

But ChatGPT also created a new problem: undifferentiated noise. “I think it’s actually a very noisy space,” Anand observed. “Getting people to understand exactly what your difference is and how to make sure that difference comes across clearly, that’s the part that becomes the new challenge. Especially when you have a bunch of solutions that only kind of get there instead of the ones that really work.”

Post-ChatGPT, CoreStory shifted to demonstrating specific technical superiority through benchmark improvements that separate real capability from marketing claims.

Segmenting Narrative by Technical Sophistication

CoreStory deploys three positioning strategies calibrated to audience depth.

For AI practitioners tracking academic benchmarks: “If you are an insider in AI and you say, hey, I can make your coding agents 44% more effective on real world engineering tasks, you will say, wow, that is amazing. That’s an super powerful benchmark improvement.”

For engineering leaders familiar with AI tooling but not research: “We often talk about the productivity boost that you’ll get from using Core Story. We talk about metrics that you can impact, we talk about the difficulty of real world engineering tasks.”

For non-technical executives: “We talk about Core Story’s ability to reverse engineer a code base into a spec, writing out all the behaviors, the user stories, descriptions of every piece of that code base in ways that both a human being or a coding agent can understand.”

The principle: technical audiences dismiss vague value propositions as marketing fluff, while non-technical audiences get lost in benchmark minutiae. Map your positioning to how each segment actually evaluates solutions.

Seeding Category Language Through Earned Adoption

CoreStory originally called their approach “requirements-driven development” before simplifying to “spec-driven development.” Rather than pitching Gartner to validate the category, they focused on getting customers to adopt the language naturally.

“We talked about it with customers and we saw that customers often changed using that language, which was great. So people started saying spec driven development or code to spec engines.”

Public demonstrations came next. “We gave some talks out there that were public, a couple at GitHub Universe, a couple out at customer sites, a couple on recordings that you can find online, where we just went out there and talked about spec driven development and what you can get from it. And we showed some demos that showed that you could actually get meaningful improvements in how you build software by writing the spec first and then using that spec to build.”

The inflection point came when influential community voices independently adopted the terminology. “Some other folks actually also picked this up. I’m super happy to say that there were some influential talks given in the AI engineering community by other people who had seen what we had done or who had inferred what we had done and started using similar terminology to describe it.”

By winter, major tech companies were building implementations. “This winter, a lot of folks started talking about tools and technologies that they had built, major open source contributions like GitHub’s spec kit that allowed you to do things with spec driven development that you could not do before.”

The lesson: category language sticks when practitioners choose to use it because it clarifies their work, not because vendors manufactured consensus. Focus on customer adoption as proof of concept before seeking broader market validation.

Positioning Against Practice Shifts, Not Products

Anand’s category insight comes from studying how movements monetize. He points to JIRA as the canonical example.

“JIRA is what is it at the end of the day? It’s a ticketing system, right? You move tickets around. And the reason that it has gotten such massive credence is not because people love tickets. In fact, people hate tickets. And people don’t necessarily love JIRA. What they love is Agile as a way to move away from what came before it, which is waterfall. And that movement towards Agile was what drove the growth of JIRA.”

CoreStory applies this framework by positioning as the enabler of AI-native engineering—the discipline that will displace Agile.

“There are a set of engineering practices that you can carry out that make these models work really well at ordinary engineering work. And that set of practices collectively is being called right now AI Native engineering,” Anand explained. Teams implementing these practices are “going, no joke, 10 times faster in terms of the amount of stuff they are shipping compared to teams that were following ordinary non AI native practices.”

CoreStory’s bet: “AI native engineering is going to be the movement that replaces Agile as the way that people choose to build software.”

The strategic implication: attach your product to emergent practice changes (how teams will work differently) rather than feature comparisons with incumbent tools. Movements create markets.

Building Multi-Channel Distribution for Different Awareness Stages

CoreStory’s three go-to-market channels map to distinct buyer journey stages.

Direct enterprise targets teams who’ve already invested in AI tooling and hit the context limitation. “These folks come and find us because they hear about AI engineering, AI native engineering. They are looking at their current landscape of tools and saying, well, I made an investment in GitHub Copilot or I made a big investment in OpenAI and yet I am not seeing gigantic gains in terms of return on investment in speed.”

Partner channels integrate with coding agents via MCP (Model Context Protocol). “Big categories of partners for us coding agents, people who are building some of these AI native engineering tools that run alongside us. The famous ones are tools like Cognition or Factory, which are great coding agents. Those guys plug in directly into Core Story using MCP. So their agent talks to our agent, we generate the code intelligence, they generate the actual ticket and pull request.”

Hyperscaler and system integrator channels distribute into modernization projects. “We go in through hyperscalers, folks like Microsoft, where we end up deploying out directly to customers who are doing activities around modernization, maintenance or AI improvements, as well as system integrators, teams that are already doing modernization and maintenance at scale and looking to add in AI layers to enhance those workflows.”

Each channel serves a different problem awareness state. Design your go-to-market to meet customers where they’re already looking for solutions.

Why Specs Become More Important Than Code

Anand’s long-term vision centers on a counterintuitive insight: in the AI era, specifications become more valuable than the code itself.

“We believe that if you are building the software layer of the future, the software development lifecycle of the future, the engineering orgs of the future, you are going to need to have a spec and a context layer attached to every single application that exists in the world.”

The reasoning: code becomes disposable as models improve, but the spec remains the source of truth. “The code can change, the code can be thrown away, rewritten. As coding agents and language models get better, that code will be transformed 5, 10, 15 times faster than you think. But the spec is the part that becomes the source of truth.”

CoreStory’s vision is to build “the best platform for understanding all the code that exists in the world and building the spec engine, the context layer that powers the AI native engineering cycles of the future.”

CoreStory’s category creation playbook offers a framework for founders building in emerging technology spaces: seed language through customer adoption rather than analyst pitching, position against practice shifts rather than competing products, design distribution for different awareness stages, and let category definition emerge from solving real problems rather than manufacturing consensus. When Microsoft and GitHub build their own implementations of your category language, you’ve won without ever touching Gartner.