Ready to build your own Founder-Led Growth engine? Book a Strategy Call

Frontlines.io | Where B2B Founders Talk GTM.

Strategic Communications Advisory For Visionary Founders

Actionable

Takeaways

Time your category noun definition strategically:

MobileIron focused exclusively on solving the problem (the verb) but waited too long to influence category nomenclature. Gartner labeled it "Mobile Device Management" when customer purchase drivers were security-focused, not management. This misalignment constrained positioning for years with no way to correct it. The framework: lead with verb, but proactively shape the noun before external analysts do it for you. Bob's doing this differently at BlueRock by distinguishing "agentic action security" from "prompt security" early, even while the broader market sorts out AI security taxonomy.

Use customer language as category discovery, not invention:

Bob's breakthrough on BlueRock positioning came from asking prospects: "How would you describe what we do to your peers?" One prospect distinguished their focus on "the action side - taking AI and taking action on data and tools" versus prompt inspection and AI firewalls. This customer-generated framing revealed the natural fault lines in how practitioners think about the problem space. The tactical application: run this exact question with your first 10-15 qualified prospects and pattern-match their language, rather than workshopping category names internally.

Engineer for the "high urgency, low friction" intersection:

Bob's filtering criteria for BlueRock's roadmap requires both dimensions simultaneously. When a prospect revealed they were building their own MCP security tools - a signal of acute, unmet pain - they also asked BlueRock to add prompt security features. Bob's framework forced a "no" despite clear demand because it would violate low friction. The discipline: if a feature request fails either test (not urgent enough OR too much friction), it doesn't make the cut, even when prospects explicitly ask for it.

Accept ICP ambiguity as a feature, not bug, of 1.0 markets:

In 2.0/3.0 categories, you can target "VP of Detection & Response" with precision. In 1.0 markets like agentic security, Bob finds buyers across three distinct orgs: agentic development teams building secure-by-default systems, product security teams inside engineering (not under the CISO), and traditional security organizations. His thesis: this lack of crisp ICP definition is actually a reliable signal you're in a genuinely new market. The response: invest in community engagement across all three buyer types rather than forcing premature segmentation.

Shift content strategy from SEO to AEO immediately:

Bob identifies the clock speed of marketing change as "breathtaking" - what worked 18 months ago is obsolete. The specific shift: ranking above the fold in Google search is now irrelevant. What matters is appearing in the answer box that ChatGPT or Google Gemini surfaces above traditional results. This isn't incremental SEO optimization - it requires fundamentally restructuring content to feed LLM context windows and answer engines rather than keyword-optimizing for traditional search crawlers.

Treat go-to-market fit as a distinct inflection point:

Bob observed a consistent pattern across MobileIron, Box (Aaron Levie), Citrix (Mark Templeton), Palo Alto Networks (Mark McLaughlin), and SendGrid (Sameer Dholakia) - all hit PMF, hired salespeople aggressively, burned cash, and stalled growth while boards grew frustrated. The missing concept: PMF proves you can create value; GTM fit proves you can capture it repeatedly. It's the "repeatable growth recipe to find and win customers over and over again." The tactical implication: after PMF, resist pressure to scale headcount and instead obsess over making your first 3-5 sales cycles systematically repeatable before hiring your second AE.

Build community as primary discovery in fragmented buyer markets:

Bob's most different GTM motion versus five years ago: "We're just out talking to prospects and customers - individual reach outs, hitting people up on LinkedIn, posting in discussion boards, engaging with the community." This isn't supplemental to demand gen; it's replaced traditional top-of-funnel. When prospects exist across multiple personas without clear titles, community presence in Reddit, Stack Overflow, and LinkedIn becomes the only scalable discovery mechanism. The benchmark: successful new tech companies have built communities of early users before they've built repeatable sales motions.

Practice systematic unlearning as second-time founder discipline:

Bob's most personal insight: "What really got in my way wasn't what I needed to learn. It was what I needed to unlearn." The specific application: he's questioning his entire MobileIron marketing playbook because "blindly applying that eight-year-old playbook to marketing or sales will end in tears." His framework: periodic gut checks asking "What assumptions am I making? How should I think about this differently?" rather than letting inertia drive execution. The meta-lesson: success creates muscle memory that becomes liability without deliberate examination. Second-time founders should actively audit which reflexes to preserve versus discard.

Conversation

Highlights

How BlueRock Learned from MobileIron’s $150M Category Positioning Mistake

Gartner labeled MobileIron as “Mobile Device Management” when customers were actually buying it for security. By the time Bob Tinker realized the problem, the category noun was set—and there was nothing his team could do to change it.

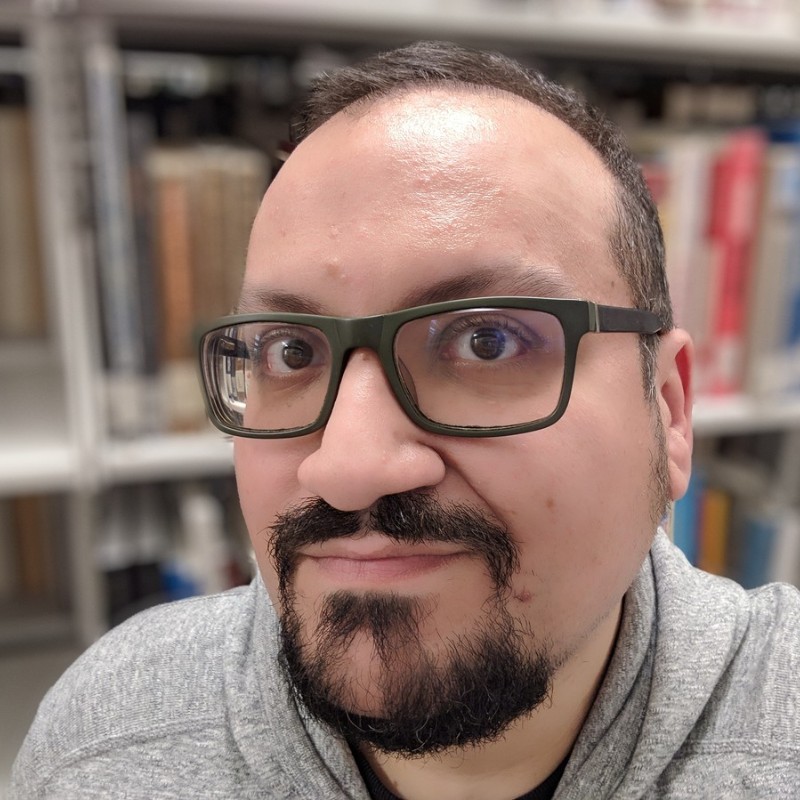

In this recent episode of Category Visionaries, Bob Tinker, CEO and Co-Founder of BlueRock, shared how this category naming misstep at MobileIron created years of positioning constraints—and the completely different playbook he’s running at BlueRock, which has raised $25 million to build agentic AI security infrastructure.

When Analysts Define Your Category Before You Do

MobileIron scaled from zero to $150 million in revenue over five years, riding the mobile wave into enterprise and going public in 2014. The company helped organizations say yes to iPhone when BlackBerry dominated corporate mobile. But a critical strategic gap emerged around category definition.

“MobileIron fundamentally is about mobile device security and mobile application security,” Bob explains. “But at some point, Gartner tagged it as Mobile Device Management, MDM, and that’s where everybody became to know it. But it wasn’t actually a management thing. Customers didn’t buy MobileIron for management, they bought it for security.”

The disconnect between Gartner’s category label and actual purchase drivers became permanent. “Once the noun got picked, it was picked and there’s nothing we could do about it,” Bob says. “I think that actually did the industry a disservice by picking that noun.”

MobileIron had focused exclusively on solving customer problems—the verb—without strategically timing when and how to influence what the category would be called—the noun. “I think focusing on the verb first is definitely the right thing to do, but I think in that case, we waited too long to focus on the noun,” Bob reflects.

Customer Language as Category Discovery Mechanism

At BlueRock, Bob is building what he calls an “agentic security fabric” to protect organizations as they deploy AI agents and MCP workflows. He sees this as a ten-times-larger opportunity than mobile’s enterprise disruption because agentic workflows “deliver huge business value and organizations are under huge business pressure to be able to deploy” them, while simultaneously creating unprecedented security exposure.

Rather than internally debating category nomenclature or immediately seeking Gartner validation, Bob deployed a specific tactical question with early prospects: “How would you describe what we do to your peers?”

One prospect’s response cut through the noise. “They said, you know what, there’s sort of this other category that’s like doing prompt security, like prompt inspection, prompt security, AI firewalls, things like that on the prompt side. And they said, you know what, you guys are different. You’re focused on the action side, which is being able to take AI and take action on data and tools. And you know what, those are going to be two different categories.”

This customer-generated framing revealed how practitioners naturally segment the AI security problem space. “There’s sort of prompt security over here, which is about talk. There’s agentic action security, which is going to be where we are,” Bob explains. “And where did that come from? It came from engaging with early members of our community.”

The implementation framework: run this exact question with your first ten to fifteen qualified prospects, then pattern-match their language rather than imposing internally-workshopped definitions. The goal is discovering how buyers naturally categorize solutions when explaining them to peers—not inventing clever marketing nomenclature.

High Urgency, Low Friction as Dual-Requirement Filter

Nascent categories generate constant pressure to expand scope. Prospects see adjacent problems you could solve. Investors push for larger TAM stories. Bob applies a dual-requirement framework to every feature decision: both high urgency AND low friction must be present simultaneously.

A prospect actively building their own MCP security tools—a powerful pain signal—asked BlueRock to also handle prompt security. The request checked the urgency box: companies building internal tools signals acute, unmet need that justifies dedicated engineering resources.

“When they ask you like, hey, could you do that for us? You’re like, oh, man, yes on one, no on the other. Like, that’s a hard thing to do,” Bob admits. But adding prompt security would violate low friction by pulling focus from agentic execution security—BlueRock’s core differentiation.

“We could go add prompt security. Like, we could, but we’re like, I think this is one of those times where we just have to be ruthless and prioritize that’s not what we’re going to do. Even though there’s a ton of companies being really successful over there.”

The discipline: if a feature request fails either test—not urgent enough OR creates too much friction—it doesn’t make the roadmap, even when qualified prospects explicitly request it. “These two things, high urgency, low friction, you get those two things combined that creates sort of a recipe for building a great company.”

ICP Ambiguity as 1.0 Category Signal

BlueRock’s buyers span three organizationally distinct personas: agentic development teams building secure-by-default systems, product security teams inside engineering (not reporting to the CISO), and traditional security organizations under the CISO.

“Right now, depending on who we’re talking to, it’s one of those three. And at some level it’s hard, right?” Bob acknowledges. This creates practical GTM friction—you can’t pull a clean list of target titles and execute systematic outbound.

But Bob has developed a diagnostic framework: “If it’s a 2.0 or 3.0 product category where you’re taking something that was there and you’re creating a 2.0 or a 3.0, you can actually have a pretty crisply defined ICP. If it’s a 1.0 in a category, it’s more likely to be the situation we’re in right now where there’s sort of different people munging around with it.”

ICP ambiguity isn’t a go-to-market execution problem to solve—it’s a market maturity signal indicating you’re building something genuinely new. The response isn’t forcing premature buyer segmentation; it’s investing in community engagement across all three persona types and letting natural patterns emerge as the market develops organizational responses to the new problem category.

Bob validates this with MobileIron’s early days: “In the beginning, sometimes it was like the security person, sometimes it was some random person in IT, sometimes it was the person like there was like the email admin who was just responsible for dealing with mobile administrators. And it was like if we had asked please take me to your mobile leader, they just would have been like, we don’t have one.”

From SEO to Answer Engine Optimization

Bob identifies a fundamental shift in content discovery that’s happened in eighteen months, not years: “It used to be everybody focused on SEO, right, to be able to get to the above the fold in Google search. Now it’s like that doesn’t matter anymore. It’s about AEO in terms of being able to get into the answer box that Google Gemini or ChatGPT puts above the folder.”

This isn’t incremental SEO optimization—it requires restructuring content architecture for LLM context windows rather than traditional search crawler indexing. The strategic implication: above-the-fold Google rankings are now obsolete as a primary discovery mechanism. What matters is appearing in the synthesized answer that ChatGPT or Google Gemini surfaces before traditional search results.

Bob also notes Gartner’s diminished influence relative to five years ago, though he still plans to invest in analyst relationships within the next twelve months. “Information and good advice is now coming from a lot of different places,” he observes, pointing to alternative intelligence sources including “turning ChatGPT loose on a bunch of analysts to come up with conclusions.”

Go-to-Market Fit as the Post-PMF Inflection Point

After stepping back from MobileIron post-IPO, Bob gave a talk at Stanford exploring what he wished he’d known as a first-time CEO. One insight became foundational: the concept of go-to-market fit as a distinct milestone between product-market fit and scalable growth.

Bob had observed an identical pattern across peer companies. “I talked to Aaron Levie at Box, Mark Templeton at Citrix, Mark McLaughlin, Palo Alto, Samir Dholakia, SendGrid. Like talk to like all my peers about sort of their journey on this. And they all had the exact same issue, which is, hey, we found product market fit. But then it was like, if you just go hire a bunch of salespeople and try and grow, like you jack up your burn rate and growth doesn’t happen and then your board gets pissed.”

The missing framework: “Product market fit does not mean growth.” PMF proves you can create value; GTM fit proves you can systematically capture it. It’s “how do you unlock a repeatable growth recipe to be able to find and win customers over and over again.”

This became Bob’s first book. The tactical application: after achieving product-market fit, resist board pressure to immediately scale sales headcount. Instead, obsess over making your first three to five sales cycles systematically repeatable—identifying which signals predict closeable pipeline, which objections consistently appear, which value propositions resonate—before hiring your second account executive.

At BlueRock, Bob applies this discipline: “How I’m thinking about it right now is how do we just nail product market fit, how do we build a scalable, go to market? How do we make customers happy? Like, if you get those things right, you’ll have lots of choices later.”

Unlearning as Second-Time Founder Discipline

Bob’s second book explored what he identifies as the most overlooked skill for experienced operators: systematic unlearning. “We spend so much time talking about what we need to learn. The thing we did not spend time talking about, which really bothered me and got in my way was what do we need to unlearn?”

For second-time founders, success creates dangerous muscle memory. “You do develop just muscle memory reflexes that allow you to be successful in sort of previous roles,” Bob acknowledges. “Anybody who’s saying, hey, eight years ago I executed this playbook to go do marketing, or executed this playbook to go do sales, or this is my playbook to go build a startup—if they just blindly apply that, it’s going to end in tears.”

Bob practices deliberate unlearning through periodic gut checks: “Rather than just let inertia drive how you do things, periodically step back and be like, what’s working? What’s not working? What are the assumptions I’m making? How should I be thinking about this differently?”

He’s applying this explicitly to marketing: “Marketing is completely different than it was five years ago and it’s actually really completely different than it was 18 months ago. Even the clock speed of the rate of change in marketing is breathtaking right now.”

The meta-lesson: previous success creates reflexes and heuristics that become liabilities in new contexts without deliberate examination. The discomfort of questioning what made you successful is real, but Bob frames it as empowering: “It’s uncomfortable, but once you get used to it it’s very powerful.”